The Sustainable Future of Fashion

Disruption in the Industry

On April 24, 2013 Rana Plaza, an eight-story garment factory collapsed in Dhaka, Bangladesh, killing 1,134 people and injuring hundreds more. This incident has become world renown as the worst industrial accident in Bangladesh’s history, resulting in boundless global criticism on labour practices in the fashion industry.

Blinded by glamourous end products, consumers in the global market are largely unaware of the working conditions for the garment workers behind their purchases. Of the ‘approximately 75 million people working to make our clothes, 80% of them are women between the ages of 18 and 35.’1 These women are often migrant workers with informal working contracts, paid low wages, and are working in poor conditions within unsafe factories that often fail to meet appropriate building codes. Bangladeshi factories have long provided low cost labour for major retailers, whose large orders of garments have created high demand for products to be made quickly and on mass. Poor labour conditions subsequently ensue, in cases workers have been required to make hundreds of items of clothing an hour and if they were not successful, they were not paid.

In the aftermath of the incident at Rana Plaza, consumers and the garment industry alike are starting to wake up to the hidden realities of what is propping up the fashion business. Concern is rising about the health, safety, ethics, and environmental impact of garment manufacturing. When it emerged that well-known brands such as UK fast-fashion retail chain Primark and Italian brand Benetton had garments manufactured in the Rana Plaza factory, consumers began to use social media to demand a better understanding of the systems and sources responsible for delivering their garments. At the beginning of 2018, over 70,000 consumers had signed a petition urging retailers to #GoTransparent. Led by a UK coalition consisting of Human Rights Watch, Clean Clothes Campaign and the International Labor Rights Forum, retailers are requested to publicly disclose the factories where their garments are being produced.

Fashion Revolution

Fashion Revolution, a movement born out of the Rana Plaza disaster as a ‘call to arms’ to fight injustice and effect change in the fashion industry, is leading the charge towards a more sustainable future for the fashion industry. Originally started in the UK by fashion industry professionals, the initiative has, five years later become the biggest activism movement of its kind in the world, with over 1,000 events taking place across 68 countries in the last week of April, to celebrate Fashion Revolution Week.

The movement focuses on mending broken lines of communication between the consumers at one end of the supply chain, and the people making their clothes at the other. With over 100 teams around the globe, Fashion Revolution has educated consumers to recognise their wardrobe as a fundamental component of the supply chain. Therefore, the power to change the way clothes are made, sourced and consumed is in the hands of those purchasing the product. Consumers are helping to facilitate greater transparency in the fashion supply chain by sharing the hashtag #whomademyclothes on social media and through online resources offered by the Fashion Revolution team, brands such as People Tree are giving garment workers a voice to respond with the hashtag #imadeyourclothes.

Source: Fashion Revolution (Instagram Account: fash_rev)

Source: Fashion Revolution (Instagram Account: fash_rev)

The Power of Transparency

Previously, the concept of transparency has meant that a company provides full, accurate, and timely disclosure of information, usually to the company’s shareholders, based on compliance requirements for reporting purposes. In large part due to the increased pressure of movements such as Fashion Revolution and heightened consumer awareness, companies are becoming increasingly aware that a lack of accountability in their supply chains can have negative implications on both their reputation and bottom line.

Source: Fashion Revolution (Instagram Account: fash_rev)

The call for transparency in the fashion industry is moving far beyond compliance, towards openly sharing information on the social, environmental and economic implications of business operations both internally and externally of an organisation. Fashion Revolution defines transparency as “public disclosure of brands’ policies, procedures, goals and commitments, performance, progress and real-world impacts on workers, communities and the environment.”

Considering the new wave of transparency among industry giants like Adidas who ranked number one in the Corporate Information Transparency Index (CITI) in 2015 and H&M, who are committed to ensuring that “everyone in its supply chain has access to a fair job”, retaining an opaque supply chain in the fashion industry is highly risky. Companies such as H&M are helping to restructure the fashion industry by ensuring that social and environmental standards are developed in factories where their products are manufactured. Ensuring protection and improvement of human rights along their value chain has most recently resulted in 100% of H&M’s garment manufacturer units in Bangladesh conducting a democratic election of worker representatives. As part of H&M’s 2018 goal, a total of 2,882 persons were elected, 40% of whom were women.

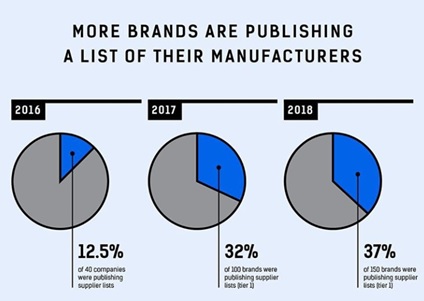

In the five years since the incident at Rana Plaza, great steps have been taken to ensure that garment production in factories is more ethical and sustainable. More brands than ever are increasing transparency and visibility of their supply chain operations by publicly disclosing their top tier manufacturers. The number of brands disclosing their Tier 1 manufacturers has increased 24.5% since 2016, according to Fashion Revolution’s 2018 Transparency Index.

Source: Fashion Transparency Index 2018

Despite these advances, Fashion Revolution discloses that a huge component of the supply chain remains underserved, with as much as 60% of retail production taking place outside of factories. There is a need to ensure that all workers, including sub-contracted workers producing garments from their homes, are included in the mapping of industry value chains. There is a long way to go before the veil is completely lifted on the working conditions of garment workers and before transparent, auditable and ethical supply chain operations across the fashion industry can be ensured.

Transparent supply chain operations and new techniques, such as Laborlink by ELEVATE‘s multi-site worker engagement strategy, designed to leverage mobile surveys to anonymously connect with workers at the factory level, is an approach to identify hidden issues within supply chains. Such pathways to assist with worker engagement are essential for businesses to effectively tackle the increasing requirements for visibility in supply chains. Although brands and retailers are beginning to understand that disclosing information about where their garments are made is important, to improve transparency and avoid to risks in their supply chain, there are multiple steps to be taken at the brand level to achieve a responsible supply chain, some of which include:

- Monitoring and managing social and environmental risks in the supply chain

- Disclosing targets aimed at improving supply chain risks, with regular progress against targets

- Delivering readable and shareable sustainability communications and reports

- Carrying out worker engagement surveys, to achieve a two-way dialogue with workers

For more information on tools and techniques available for increasing visibility in supply chains, contact kelly.cooper@csr-asia.com.

Recommended Reading:

Adidas Sustainability Report 2015: https://www.adidas-group.com/media/filer_public/9c/f3/9cf3db44-b703-4cd0-98c5-28413f272aac/2015_sustainability_progress_report.pdf

BBC This World: Clothes to die for, Rana Plaza factory collapse: http://www.fair-t.com/bbc-world-clothes-die-rana-plaza-factory-collapse/

Fashion Revolution website: https://www.fashionrevolution.org/

Fair Labor Association; Toward Fair Compensation in Bangladesh: Insights on Closing the Wage Gap, April 2018 http://www.fairlabor.org/bangladesh-2018

H&M Sustainability Summary 2017: http://about.hm.com/en/media/news/general-news-2018/hm-sustainability-report-2017.html

Human Rights Watch; Follow the Thread, The Need for Supply Chain Transparency in the Garment and Footwear Industry, April 2017: https://www.hrw.org/report/2017/04/20/follow-thread/need-supply-chain-transparency-garment-and-footwear-industry

The Five Years of Fashion Revolution by Carry Somers and Orsola de Castro: https://www.fashionrevolution.org/the-five-years-of-fashion-revolution/